Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Behavioral Design Fellowship

I worked with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center as a Behavioral Design Fellow over a three month period. As a part of a three-fellow team we consulted with the Design and Innovation Group (DIG) and their team of multi-disciplinary designers to develop a methodology that promotes behavioral science best practices. It was a unique challenge because we intentionally took a collaborative design approach with the DIG team. We were supervised by a Behavioral Scientist and DIG’s Creative Lead through three design sprints to create the B-Card methodology. The B-Card methodology was developed specifically for DIG’s designers working in the service oriented health care space but the methodology can easily be adapted for any industry. Our focusing design question was:

"How might we incorporate behavioral science insights into the dig design process?"

SUMMARY

Primary Challenge: Creating a service design solution to inject behavioral science best practices into the design process

Secondary Challenge: Reconciling the linear nature of a behavioral science process with the iterative nature of a design process

Format: Design methodology and interactive framework

The Team

Close up of the ‘Emotion’ B-card

.

Dani Beecham, MFA Design and Technology, Parsons School of Design

David Baum, MFA Candidate Transdisciplinary Design, Parsons School of Design

Anjali Bhalodia, MFA Candidate Transdisciplinary Design, Parsons School of Design

user interviews

The first step in our process was to gain an understanding of how the DIG team’s design process worked and where behavioral science interventions had succeeded and failed. We took 2.5 weeks to conduct user interviews with all but two members of DIG along with the staff behavioral scientist and the Creative Lead to gain a retrospective of past case studies. We also sat in on prototyping sessions for current projects as observation. It was important to us that we respected the anonymity of the interviewees because of the sensitive nature of work dynamics so we de-identified all of the feedback and insights.

We collaborated to develop the script and started by white boarding some of our key questions to refine and strategize the user interview script.

A list of initial questions we hoped to answer through user interviews.

Refined discussion guide for user interviews

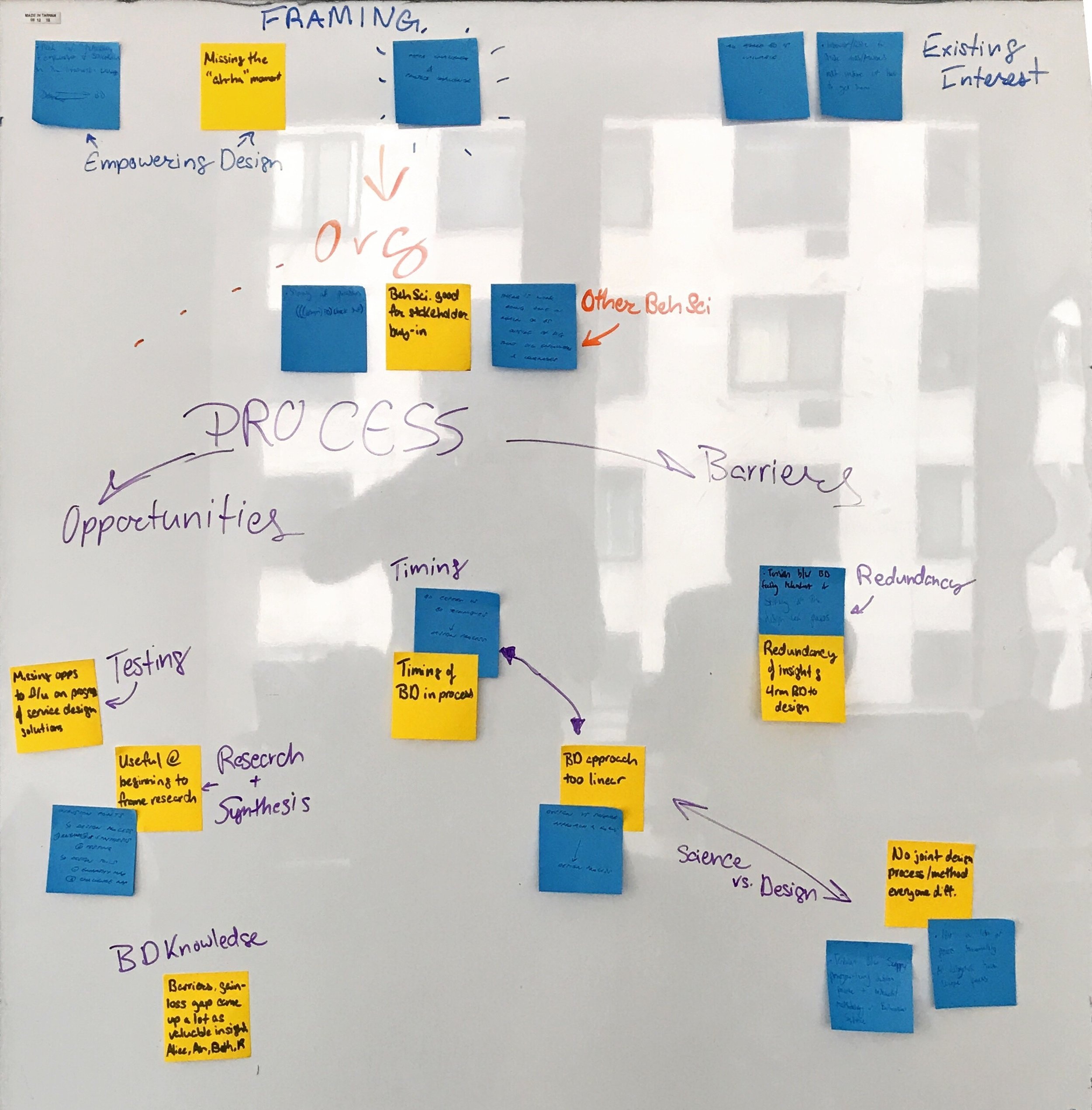

After completing user interviews with the majority of the team we worked together to synthesize the feedback. I led a white boarding session to map the feedback to certain phases in the design process and identify patterns. The goal of this session was to help us develop our hypothesis. At this phase we still hadn’t formed an opinion on what approach might have the most positive feedback from the DIG team. Mapping feedback patterns helped us develop the next model that grounded our hypothesis.

Click to expand

Synthesizing insights and identifying themes from user interview feedback.

Click to expand

Refined feedback map and system model

Prototype 1

Goal 1: Validate hypothesis on Behavioral Science injection points.

Goal 2: Generate case study examples of behavioral science principles being observed or applied by DIG members.

During one of our discussion sessions I sketched the above models based on the insights we gained from the user testing sessions. We confirmed that the team largely followed a traditional iterative design model with an additional end phase to secure internal stake-holder buy-in before deployment with staff or patients. Historically, collaboration with behavioral science consultants had varying levels of success due to a clear friction between behavioral science’s linear and sterile scientific process requiring sterile conditions and controlled variables and design’s flexible, iterative process requiring adaptability and rapid prototyping. It was important for us to accurately depict the team’s design process and begin forming our hypothesis on how best to inject behavioral science into existing phases.

Behavioral topline worksheet annotated with the number of times users encountered the behavior. We found that ‘identifiable victim effect’ had the most instances.

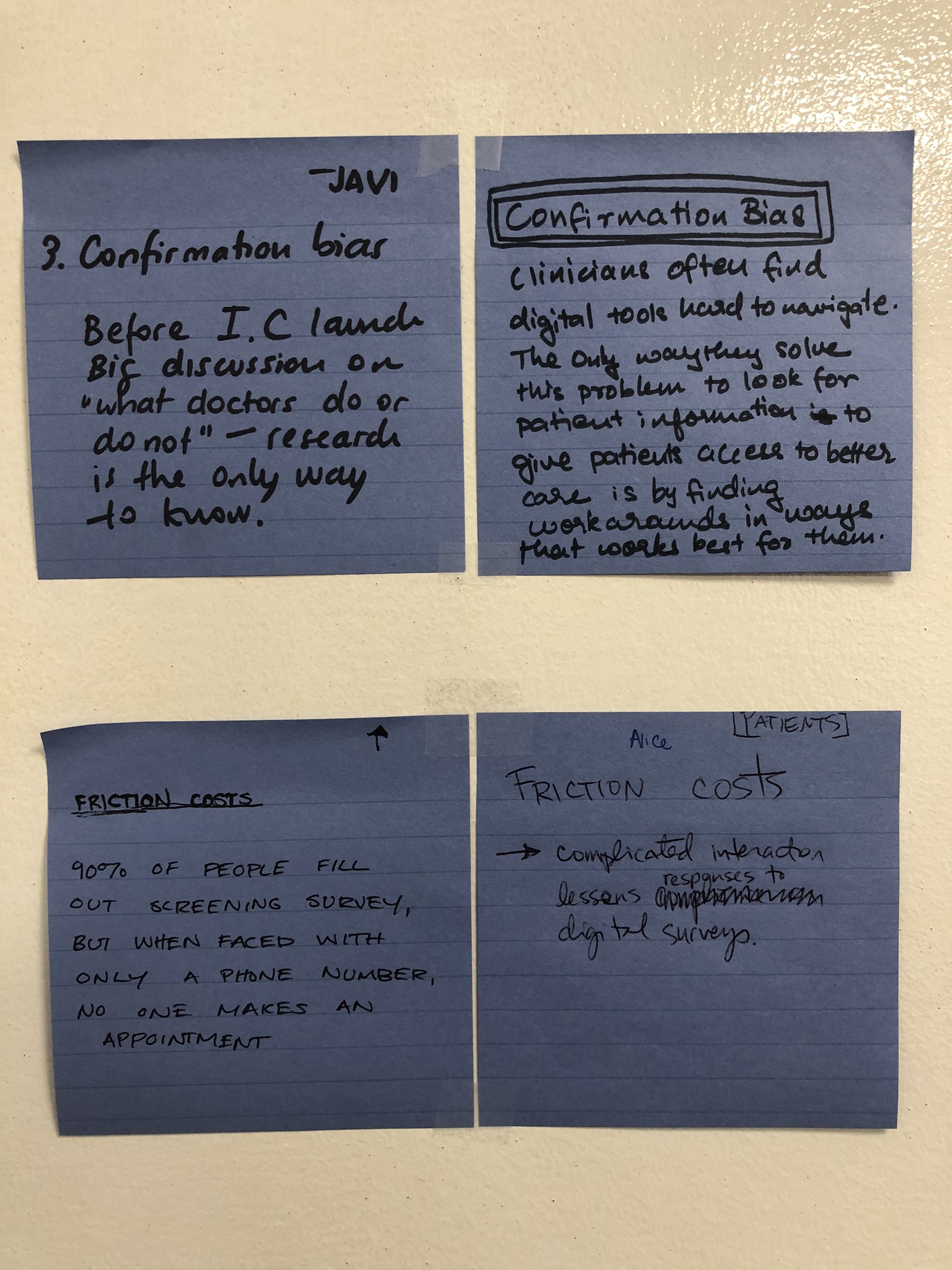

We scheduled three workshops to test prototypes. For the first prototyping workshop we wanted to get feedback on the system model and dive deeper into some of the specific behavioral science approaches. We conducted literature reviews of behavioral science theories and summarized some of the most relevant theories with guidance from the DIG team’s Behavioral Scientist. We collected 20 top line principles and asked DIG’s designers to review the toplines and choose three that they had encountered in past projects. Finally, we asked them to capture their feedback on post-it notes and share back with the group.

Designers summarized cases where they encountered “loss aversion” and “omission bias”

Designers summarized cases where they encountered “confirmation bias” and “friction costs”

Observations

We noted that certain behavioral science principles were more heavily encountered than others. For instance, three designers reported encountering the “identifiable victim effect” in some aspect of their work but principles like “gamification” and “optimism bias” weren’t identified by any of the designers. We also noted that some designers misidentified some of the top lines or conflated their definitions. We also realized that some of the case summaries could be attributed to multiple behavioral science principles.

When we presented the process model the DIG team made an important annotation. They agreed with the overall model and the behavioral design “infusion points” but noted that stakeholder buy-in happens at multiple points throughout the process so we modified the model to reflect those “stakeholder humps.”

Click to expand

Initial system map depicting a summarized version of the DIG team’s design process. The orange lines signify the phases where behavioral science approaches had a positive impact on overall project outcomes. The dashed orange lines signify the phase where behavioral science had yet to be incorporated but showed promising potential for positive outcomes.

Click to expand

During the workshop we presented the model and the DIG team annotated the model to reflect the additional stakeholder buy-in “humps” that happen throughout all phases in the process. The team agreed BD principles can be leveraged at these pivot points.

DIG’s design team working through the first prototyping session

Feedback

DIG thought exercise felt validating - connecting behavioral top lines to current & past project problem spaces was helpful

Incredibly useful to see everything explicit

On the road to being very actionable

In its current form its easy to use it as confirmation bias rather than anchors

Great to ground it in cancer care - maybe conditions that are broad constraints that could happen anywhere

Its been hard to manipulate this into our work because it hasn’t been physical

Could be something that lines up to our observations

Proof of concept today and if we do the other things, it’ll be meaningful

Discussion around evaluative testing and where it happens was interesting - is there a way to overlay this and the behavior guide

Canvas of sorts that bits and pieces can be interrogated

Prototype 2

Goal 1: Test the designers’ ability to problem solve within a pre-defined framework

Goal 2: Synthesize relevant behavioral design principles to frame the designers’ problem solving approach

For the second prototype we decided to stick with the workshop format. Watching the designers interact with the prototype in real-time helped us gain better insights and helped us gauge buy-in from the designers which was critical. We had more case study examples of the DIG team’s work overlapping with behavioral science and we had buy-in for our initial approach to infuse behavioral design to support the prototyping, discovery, buy-in, or evaluative research phase.

Stakeholder Vision

We debriefed as a team and discussed the path forward with our advisors- DIG’s Creative Lead and DIG’s Behavioral Scientist. The Creative Lead shared her vision for the framework- to make prototyping more robust and grounded in scientific insight.

With their insight we chose to focus on a tool that would support the designers in their design sprints and guide their research analysis and prototyping. Supporting the designers in their presentations to stakeholders remained an important secondary goal but the thought was if designers were grounding their prototypes in behavioral science, it would make it easier to present to stakeholders from that perspective.

Whiteboard sketch session depicting our worked through example using the first iteration of the Behavioral Design framework

co-design over prescription

We discussed different ways we might guide DIG designers through a behavioral design analysis without being too restrictive. Based on interview feedback we knew past attempts at incorporating behavioral science had failed in part due to their rigidity. However, we knew based on observation that the DIG team were accustomed to working through problems on paper and discussing as a group.

I led a white boarding session to test an idea. I thought if we could start by getting the designers to identify a single pain point at play, we could ask them to apply a behavioral science principle and give them relevant “considerations” to apply to their natural solution finding process. We chose one of the case studies the DIG team shared with us and worked through the framework.

Observation

We presented the above images to the DIG team in a second workshop. We asked them to form three groups and each fellow observed a group. We started by asking them to identify a current or recent problem area that they were working on and come to a consensus on which case study they wanted to tackle as a group. Once they identified the problem space we asked them to follow the directions on the first sheet and work through the problem. My team and I were there to observe and clarify. We captured great feedback on each sheet that the designers annotated.

Feedback

Unfortunately, our worksheets were accidentally thrown out over the weekend before we could capture them. We did our best as a team to recall insights. The major feedback points were the following:

Some of the groups found it more natural to ideate on the solutions without referring to the behavioral science top lines; one group had to be instructed to use the top lines to frame their insights

It was helpful to have the behavioral science top lines available as visible references to prompt the designers to reframe some of the problem spaces that they encounter

Designers thought it would be useful to frame some of the insights in a healthcare context

We asked designers to generate pain points based on a predefined list of behavioral science top lines and then use one of those pain points to ideate further with other behavioral top lines that might apply. Several of the designers found this confusing

Final Prototype

We knew we were on the right track with the framework and decided to iterate on the directions and layout of the framework. The largest pain point from Prototype 2 was that some of the designers still weren’t finding it natural to apply the behavioral science insights to their solution-finding. We discussed ways to make behavioral science feature more prominently and incorporate more insights that were relevant to a healthcare context. We decided to try and prototype cards that explicitly guided the user from context to solution.

I sketched the below paper prototype to demonstrate how the cards might interact with our reiterated framework by prompting designers to match a card their analysis. I envisioned cards being two-sided. One side would be an “if statement” — if you observe this behavior then turn the card over and try to keep the following insights in mind. I got buy-in from my teammates and we began sketching and formatting.

We pulled from content already generated by DIG’s Behavioral Scientist from our past prototyping sessions and tried to summarize some of the content and extrapolate insights. I used my previous experience in the healthcare industry to write examples framed in a healthcare perspective to include on the “observe” side of the cards. We hoped that grounding the cards in relevant examples would also help the designers narrow in on the most useful set of insights and error prevent some of the misidentification that happened in the first session.

Observation

The final prototype testing session was very successful. Designers grouped to work on a current case and again we sat in and observed. The instructions seemed to be more intuitive and generated more solutions than prototype two. It was actually difficult to call time and get the designers to switch gears to give us feedback. The best indicator that the tool was successful came as we were leaving the session. The DIG team asked if they could keep the copies of the framework and cards to use in their next meeting.

Feedback

Could have benefited from more formatting to increase readability on the “strategize” side of the card.

Examples weren’t referred to as much- may be due to DIG team already being familiar w/ principles form previous workshops

Felt natural to take time during the “Describe” portion to report back to co-collaborators on constraints and factors

Used key words from the “strategize” side as inspiration to ideate on solutions

“Distill” needed a little more prompting to help the designers figure out what to prioritize

Positive response to “distill” and “strategize” having more space in the formatting- prompts them to expand their thinking

Could explore color-coding to facilitate actions

Brought new cards into play even after matching to help ideate on the strategies; lots of overlap

Good iteration from last prototype

Useful for process-based challenges around working together and collaboration

Would be helpful in a design sprint scenario

Kept copies to use in the next meeting

Even having the list of toplines visible can serve as a prompt to incorporate it in your process.